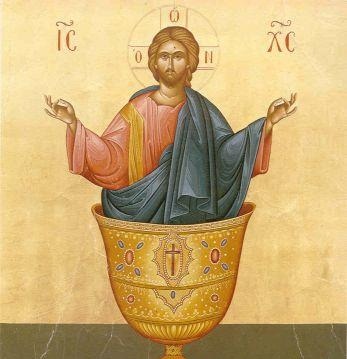

The principal worship service of the Orthodox Church is the ritual meal known as the Holy Eucharist (from the Greek εὐχαριστία, meaning “thanksgiving”). The celebration of the Eucharist is as old as the Church itself, going all the way back to Jesus’ institution of the meal in the upper room with his disciples “in the night in which he was betrayed” (1 Cor 11:23-26). Beginning in Jerusalem and then spreading throughout the world, Christians have faithfully followed Jesus’ commandment to “do this in remembrance of me.” Why is this the principal form of Christian worship? Jesus’ own words answer this: “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you” (John 6:53). In the Eucharist, we offer ourselves as a living sacrifice to God (Romans 12:1), and God makes present to us in the bread and the wine Christ’s one, complete, and sufficient sacrifice on the Cross, so that in them we may partake of Christ’s very life, his Body and Blood: “Take, eat, this is my Body which is for you…” (Luke 22:19-20).

As the Church grew to include various people groups and their languages, the original Eucharistic service from Jerusalem was developed and adorned by those various peoples according to their unique musical and artistic expressions, poetic traditions, and senses of beauty, dignity, and piety. The largely Greek speaking eastern half of the Roman Empire (later called the Byzantine Empire) would come to call the celebration of the Eucharist “the Divine Liturgy” (Liturgy from the Greek λειτουργία,meaning “work of the people”). In the western part of the Roman Empire, where the legacy of old Roman culture was more established and Latin was the lingua franca, the Eucharist came to be called the “Missa,” or “the Mass” in English. This word comes from the final dismissal of the service in Latin: “Ite, missa est” (or “Go, this is the sending out”). Though many of the sights, sounds, and particular words of the Eucharistic services of the Eastern and Western traditions are different, the structures of both are very much alike, because both grew organically out of that original primitive Liturgy of the earliest Christians in Jerusalem.

East and West

The basic shape of the Liturgy in both the East and the West is two-fold, consisting of the “Liturgy of the Catechumens” and the “Liturgy of the Faithful.” These are so named because in the first centuries of the Church catechumens (or those who were still being prepared to be received into the Church as full members) would be dismissed after the first part, leaving only the full members of the Church (the “faithful”) for the second part. Because the practice of dismissing the catechumens between each part has largely disappeared, the two main parts of the Liturgy are now sometimes called after what their foci are: the “Liturgy of the Word” and the “Liturgy of the Eucharist.” In both Eastern and Western Liturgies, these two main parts can be further divided as follows:

The Liturgy of the Catechumens

Entrance – This includes the fixed features of the Great Litany and three antiphons in the East, and the Kyrie and Gloria in the West. It also includes chants proper to the day, being the Troparia and Kontakia in the East, and the Introit and Collects in the West.

Proclamation – Passages of Scripture are proclaimed, in both East and West, accompanied by special chants (the Gradual & Alleluia or Tract in the West) with verses for the day.

Homily – The general custom in both East and West is to follow the Gospel proclamation with a homily, usually based on the Gospel passage or theme for the day.

The Liturgy of the Faithful

Nicene Creed – The word creed comes from its first word in Latin: Credo (“I believe”). The East calls the Creed the Symbol of Faith.

Oblation – The gifts of bread and wine are reverently brought from the preparation table to the Altar. This is done solemnly but directly in the West, while in the East the gifts are processed out into the Nave in the Great Entrance. The Eastern Liturgy continues with the Cherubic Hymn, and in the West the proper Offertory chant of the day is sung, often followed by some appropriate hymn. The Western offertory prayers are prayed at this point, being analogous to what takes place before the Eastern Liturgy during the Prothesis.

Consecration – In both Eastern and Western rites this begins with the priest’s exhortation to the people: “Lift up your hearts” (Sursum corda). And for both rites, the following Eucharistic prayers share the same essential features: addressed to the Father, includes Jesus’ words of institution, invokes the Holy Spirit to change the bread and wine into Christ’s own body and blood, and concludes with a Trinitarian doxology.

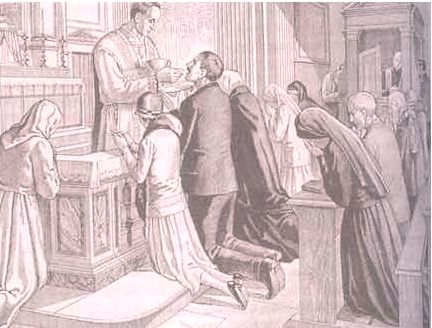

Communion – The faithful then receive both the Body & Blood (administered with a spoon in the East andusually intincted and received together in the West) while hymns may be sung. Bread that has been blessed at the Offertory (not consecrated) is offered to all (antidoron in the East, panis benedictus in the West)

Dismissal – After the remaining Eucharist is properly consumed and the holy vessels cleansed, the priest dismisses and blesses the people. In the West, the Liturgy/Mass usually concludes with the Prologue from the Gospel of St. John (the “Last Gospel”) and a recessional hymn may be sung.